Botanical Name: Cimicifuga racemosa L, Actaea racemosa L

Black cohosh was once classified with the Genus name Cimicifuga but today the Genus name Actaea is considered the correct scientific name.

The old Latin genus name Cimicifuga derives from Cimex, the genus name of the bedbug and the Latin verb “fugare” meaning to repel indicating that the unpleasant smell of the plant was used as an insect repellent.

Other Common Names: Black snake root, bugbane, rattleroot, rattletop, rattleweed, snakeroot, black bugbane, squaw root, serpentaria (Spanish), Traubiges Wanzenkraut, Schwarzes Wanzenkraut (German), herbe aux punaises (French), silfurkerti (Icelandic), sølvlys (Danish), läkesilverax (Swedish), klaseormedrue (Norwegian).

Habitat: Black cohosh is native to the United States and Canada and is particularly found in northern Oregon, Washington state, and Ontario. It is now cultivated in many European Mediterranean countries due to commercial demand.

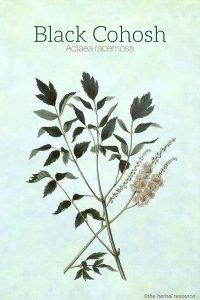

Description: Black cohosh is a perennial plant of the Ranunculaceae (buttercup) family.

It has radical compound leaves with sharply toothed margins and in summer produces a compound raceme of white staminate flowers. It grows up to a height of 2 meters and is found particularly in shady forests.

Plant Parts Used: The rhizome. The rhizomes are harvested in autumn from plants that are at least two years old, but preferably older.

The herb has a bitter and sharp flavor and a slightly unpleasant odor and it is generally taken as a standardized extract in tablet form, although it is also available as a dried root and a tincture.

Black Cohosh Therapeutic Benefits, Traditional Uses and Claims.

Active Ingredient and Substances: Black cohosh’s main constituents are cimicifugin, triterpene glycosides, isoflavones, tannins, salicylic acid, alkaloids (trace only), fatty acids (ferulic acid, iso-ferulic acid, mucilage, resins, sugars, and starch.

Furthermore, eight new triterpene glycosides, called cimiracemosides A-H, have been identified.

Ferulic acid and iso-ferulic acid are the two substances that are believed to be responsible for the anti-inflammatory action of the herb.

Traditional Use of Black Cohosh in North America

In North America, the Native Americans and the early European settlers used the root (rhizome) of black cohosh as a remedy for irregular menstruation, to aid in childbirth and for rattlesnakes bites.

Other traditional uses of the herb included treatment for malaria, rheumatism, back pain, abnormal kidney function, cough, sore throat, and fever. It was also used as a mild sedative.

Just as other important medicinal plants native to North America, such as the echinacea (Echinacea purpurea) and saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), black cohosh was early on introduced to Europe.

The herb was imported to Germany in the late 1800s where it was primarily used in homeopathic form until 1930 to treat gynecological disorders.

A Useful Remedy for Menopause

Modern day use of the herb is most commonly for menopausal symptoms but also pre menstrual syndrome (PMS) and irregular periods.

As women reach menopause, the signals between the ovaries and pituitary gland begin to diminish, which in turn reduces the production of estrogen, and increases the secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH). Hot flashes and other acute symptoms of menopause are thought to be related to these changes.

Early studies done on rats suggested a hormone-like effect of black cohosh. One of these study found that constituents in black cohosh did connect to the estrogen receptors in the uterus.

Another study found that the herb caused a decrease in the concentration of LH in the blood. The conclusion at that time was that black cohosh had a mild estrogen effect and also reduced the amount of LH, both believed to contribute to reducing hot flashes in menopausal women.

In recent years, however, both animal and human studies indicate that these early findings of the estrogen effect of black cohosh are not necessarily accurate. In a study done on mice and rats, it was found that black cohosh does not have any estrogenic properties.

The theory of the estrogen effect of black cohosh was further weakened when one of the best studies to date looked at the effect of the commercial black cohosh extract Remifemin® on menopausal women between 43 and 60 years. The women were administered either 40 or 127 mg of the extract daily for three months.

Although the frequency and severity of the hot flashes improved markedly and was similar at both dosages, there was no estrogen-like effect noted at all.

The conclusion was, therefore, despite earlier findings that black cohosh does not contain any phytoestrogens, and that women experience menopause symptoms should not look to it as an estrogen replacement.

In addition, isoflavones, a group of substances that include all phytoestrogens, rarely occur in plants other than those belonging to the pea family (Fabaceae ) such as soy (Glycine max) and red clover (Trifolium pratense). Black cohosh belongs to the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae).

Black cohosh is still, despite having probably no hormonal effects, regarded as one of the best natural options for a relief for hot flashes during menopause and it does not cause serious side effects and potential health risks (eg. increased risk of cancer) as estrogen substitutes have been known for.

An overview of eight German clinical trials on the effectiveness of black cohosh as a treatment for symptoms of menopause and which was published in the Journal of Women’s Health, concluded that the herb is safe and effective, and may be suitable as an alternative to estrogen replacement therapy for women who do not want to use estrogen substitutes or where the use of such substitutes can be harmful.

Some research has suggested that black cohosh in combination with St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) is useful for both hot flushes and mood swings caused by the menopause.

Other Uses of Black Cohosh

Black cohosh has been used as a treatment for osteoporosis and is regarded to be helpful for some rheumatic disorders, such as arthritis. Wild yam (Dioscorea villosa) is often used in combination with black cohosh in that regard.

Resins present in the herb have been shown to expand the peripheral blood vessels, and along with its calming effect, it may be useful as a remedy for high blood pressure, reducing headaches and tinnitus.

Black cohosh has antispasmodic and muscle relaxant properties and has been used as a relief and treatment for coughs, asthma, and pertussis.

Research has shown that the salicylates in the herb act as an anti-inflammatory, which could explain the traditional use of it among the Native North Americans for nerve and muscle pain.

It is often found in combination with other herbs thought to be of benefit for women’s health e.g. menstrual cycle and menopause.

Dosage and Administration

Traditionally, black cohosh has been used as a tea where 1 teaspoon (5g) of the dried root is added to one cup of hot water. Some literature recommends three cups daily.

The herb is not thought to be particularly effective when it is used in tea form and is preferably used today as standardized liquid extracts, tablets or capsules. One of the more popular standardized commercial product on the market is ]Remifemin®.

When using commercial products the manufacturer’s instructions should be followed.

Potential Side Effects of Black Cohosh

Side effects of black cohosh are generally mild and rare. They include stomach upsets and nausea. Other side effects that have been noted are low blood pressure, headache, dizziness and allergic reactions.

Some black cohosh products have been associated with serious liver conditions but this has not been confirmed and is most likely to be due to low-quality products.

There are no known interactions between this herb and conventional medicine although it is suggested not to take it with high blood pressure medication. Pregnant and breast-feeding women should not take this herb.

Supporting References

Atkins, Rosie, et al.: Herbs. The Essential Guide for a Modern World. London, Rodale International Ltd. 2006.

Barnes, Joanne; Linda A. Anderson & J. David Phillipson: Herbal Medicines. A guide for healthcare professionals. Second edition. London, Pharmaceutical Press 2002.

Blumenthal, Mark: Herbal Medicine. Expanded Commision E Monographs. Austin, Texas, American Botanical Council 2000.

Blumenthal, Mark (senior editor): The ABC Clinical Guide to Herbs. Austin, American Botanical Council 2003.

Blumenthal, Mark: European Health Agencies Recommend Liver Warnings on Black Cohosh Products. HerbalGram 72 (2006) s. 56-58.

Brown, Donald J.: Herbal Prescriptions for Health and Healing. Roseville, Prima Health 2000.

Crow, Tis Mal: Native Plants, Native Healing. Summertown, Native Voices 2001

Foster, Steven and Rebecca L. Johnson: Desk Reference to Nature’s Medicine. Washington D.C., National Geographic 2006.

Gruenwald, Joerg et al.: PDR for Herbal Medicines. Fourth Edition. Montvale, New Jersey, Thomson Healthcare Inc. 2007.

Hoffmann, David: Herbs for a Good Night’s Sleep. New Canaan, Keats Publishing, Inc., 1997.

Hutchens, Alma: Indian Herbalogy of North America. Boston, Shambhala 1991.

opular Herbs. Roseville, Prima Health 2000.

Mills, Simon & Kerry Bone: The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety. St. Louis, Elsevier 2005.

Williamson, Elisabeth M.: Potter’s Herbal Cyclopaedia. Essex, Saffron Walden 2003.

Woolven, Linda & Ted Snider: Healthy Herbs. Your Everyday Guide to Medicinal Herbs and Their Use. Ontairo, Fitzhenry & Whiteside 2006.

Thordur Sturluson

Latest posts by Thordur Sturluson (see all)

- What is the Difference Between Hemp and Marijuana? - June 3, 2019

Leave a Reply