Botanical Name of Horsetail: Equisetum arvensis, Equisetum arvense.

Other Common Names: Bottlebrush, shave grass, corncob plant, scouring rush, field horsetail, pewterwort, paddock-pipes, Dutch rushes, snake pipes, small scouring rush, åkersnelle (Norwegian), cola de caballo (Spanish), prêle des champs (French), Acker-Schachtelhalm (German).

Habitat: Horsetail is native to both North America and Europe. It is one of only a few Equisetum survivors from the dinosaur era.

In parts of Northern America, Canada, and Europe it is often considered a rather bothersome weed because of its prolific tuber system.

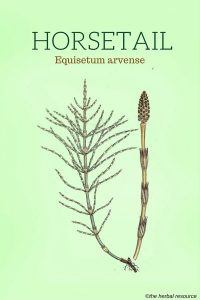

Plant Description: Horsetail is a perennial plant of the Equisetaceae or the horsetail plant family. It is a unique plant because it has two very different stems.

In the early spring, it grows a stem that looks somewhat like asparagus. Later in the Summer, the stem appears as thin, green and somewhat feathery.

Plant Parts Used: The above ground parts of the green summer shoots are collected and used fresh. The lower dark portion of the stem should be removed before the plant is dried and all discolored parts of the dried herb discarded before it is stored for later use.

Therapeutic Benefits and Uses of Horsetail and Claims

Horsetail contains silicic acid, saponins, flavonoids, sterols, tannins, potassium, aluminum salts, manganese, magnesium, sulfur and calcium.

Historically, horsetail has been used to stop bleeding, repair broken bones and as an herbal remedy for arthritis.

It has also been beneficial in the treatment of dropsy, gravel and kidney infections, including ulceration and ulcers in the urinary passages.

Because horsetail has the ability to increase urine production, (a diuretic), it gained popularity as an herbal treatment of kidney stones, edema and urinary tract infections as well as cystitis.

This property can be attributed primarily to the presence of flavonoids.

The herb has been used to treat inflammation of the prostate gland, or benign enlargement of the prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia, BPH).

It is often used in combination with smooth hydrangea (Hydrangea arborescens) in the treatment of prostate problems. It has also been used as a supportive treatment for gout.

Before the advent of synthetic and more effective treatments, the herb was the principal remedy for tuberculosis.

Because horsetail is rich in silica and silicic acids it could be beneficial as an herbal treatment for osteoporosis.

Furthermore, silica may increase the production of white blood cells, which can result in a stronger immune system and improves the body’s resistance to infections. Silica also increases the elasticity and resistance of the skin and connective tissue.

The herb has hemostatic (promotes clotting by bleeding) properties and helps stop bleeding of ulcers and controls excessive menstrual bleeding.

The silicic acid content of the herb stimulates the absorption and utilization of calcium and prevents the deposition of fat in the arteries. The astringent properties strengthen vein walls and can be helpful for varicose veins.

Topical preparations of the herb can be used to heal wounds, sprains, fractures, and burns. It has been used as an herbal treatment for rheumatic conditions and skin problems such as dandruff.

Some studies support that horsetail could be helpful in improving memory and cognitive function.

The plant also had other uses than as a medicine. The dry stems have a high content of crystalline silicon and have been used to scrub metal and polish tin and wood. In the past, the herb was also used to dye wool yellow.

Dosage and Administration

The most common way that horsetail is administered is in a tea.

Normally it is prepared by pouring boiled water over 2 to 3 grams of horsetail herb. Boiling time is five minutes. After it is boiled it needs to stand for approximately 10 to 15 minutes. Then it can be strained. Drink the tea between meals during the day.

- For internal use: 6 g daily (the German E Commission recommends this dosage)

- As an herbal infusion: 4 oz three times daily

- [easyazon_link identifier=”B00KLGWAJW” locale=”US” tag=”herbal-resource-20″]As a tincture[/easyazon_link] (1:5): 1 to 4 mL three times daily

- For external use such as compresses: 10 g of herb per 1 liter of water daily

Side Effects and Possible Interactions of Horsetail

The herb horsetail is not without its side effects.

These include electrolyte imbalance and deficiency of thiamine.

If used over a long period or if too much alcohol is consumed while on horsetail supplements, topical application may cause skin problems.

The herb can produce nicotine toxicity with symptoms such as nausea, muscle weakness, fever, abnormal pulse rate.

The herb’s diuretic effect can cause loss of potassium, which in turn might increase digitalis toxicity.

If horsetail is used with Benzodiazepines, Disulfiram, or Metronidazole, it may cause a disulfiram-like reaction. Use of it in conjunction with other medicines, which lead to depletion of potassium such as corticosteroids, diuretics, and laxative stimulants, increases the risk of hypokalemia.

Excessive use of licorice with horsetail should be avoided as this combination may lead to cardiac toxicity and also a loss of potassium.

Those who should keep away from horsetail include expecting or nursing women, people with a weak heart, people prone to thiamine deficiency such as those who consume excessive alcohol and those who are taking potassium wasting diuretic, a cardiac glycoside (Lanoxin), a corticosteroid, or licorice.

It must be kept in mind that sometimes the liquid extract contains 25 percent alcohol and hence shouldn’t be used with Disulfiram, Metronidazole, and Benzodiazepines.

Other Resources on Horstail

Horsetail – Ancient Wonder, Modern Medicine

Supporting References

Volák, Jan & Jiri Stodola: The Illustrated Book of Herbs. London, Caxton Editions 1998.

Skenderi, Gazmend: Herbal Vade Mecum. 800 Herbs, Spices, Essential Oils, Lipids Etc. Constituents, Properties, Uses, and Caution. Rutherford, New Jersey. Herbacy Press 2003.

Mills, Simon & Kerry Bone: The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety. St. Louis. Elsevier 2005.

Hoffmann, David: Medicinal Herbalism. The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Rochester. Healing Art Press 2003.

Foster, Steven: 101 medicinal herbs. Loveland. Interweave Press 1998.

Balch, Phyllis A.: Prescription for Herbal Healing. New York. Avery 2002.

Thordur Sturluson

Latest posts by Thordur Sturluson (see all)

- What is the Difference Between Hemp and Marijuana? - June 3, 2019

Leave a Reply